Auckland

After working  since 1962 on creating Milton Keynes, a new city for 250,000, I took a trip around the world. I visited New Zealand where my brother lived and met Malcolm Latham, then Planner for the Auckland Region. He was notable for his breadth of vision and his positive attitude.

Following my work for the Commonwealth Development Commission on St Lucia in the Caribbean and my growing dissatisfaction with the lack of any sense of a whole city image for Milton Keynes under Walker, I decided to try to persuade Fred Roche to give some attention to this lack of a vision. I encouraged Stroud Watson to come to Milton Keynes to help me with this and asked Fred Roche to let me show what I could do – but he would not.

I was then contacted by Malcolm Latham from Auckland who told me that a new post of âDirector of Planning and Social Developmentâ was being created within Auckland City Council and suggested that I apply. Applicants from New Zealand and Australia had earlier been rejected for the position, but I applied and was flown out for interview and the post was offered to me.

Having been intimately involved in the creation of a new city, I thought it would be interesting to have a go at managing and extending an existing city in a developing country.

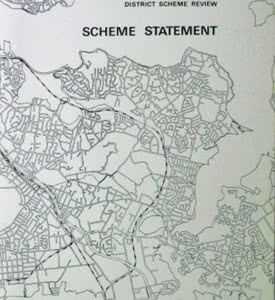

Although not New Zealandâs capital, Auckland was the dominant and fastest growing urban area. The Cityâs statutory plan was due for review but preparations and resources were well behind schedule and if the plan was not reviewed by the due date then it could all be up for challenge – so it was urgent I took up my position.

The City had an inspired Mayor, Sir Dove-Myer Robinson who had produced radical proposals for Auckland including rail based public transport. The Council was at first ruled by âgentlemanlyâ right-wingers, Councillors Ferguson, Â Dawson and Salmon. However an assertive right wing led by Jolyon Firth was coming to ascendency, they were quietly supported by many of councilâs senior staff. The political opposition was by a small group of Labour members, Jim Anderton and Cath Tizard. The effect was that Robbieâs foresight was effectively squeezed between these competing and negative pressures.

The new Department was formed from two sections which had been within the City Engineerâs Department under the leadership of a person to whom both âPlanningâ and âSocial Developmentâ were equivalent to the most extreme aspects of radical socialism! When I arrived on the plane in Auckland there was a message awaiting me to go to a secret meeting held away from Councilâs premises with the Town Clerk and two other senior officers as the Planners were threatening to go the Mayor with their complaints. It was up to me to sort them out and to do this I insisted on becoming a member of the Executive Management Committee.

The Planning system in New Zealand resembled the old 1932 Town Planning Act in UK with zoning and a right of development. It derived from the notion of the sub-division of virgin land and as a consequence it was more like Building Regulation, which demanded certainty, was extremely legalistic and depended on precise controls, often derived from plot boundaries and location. This required of Planners a very rigid approach with little scope for the imaginative, creative and innovative work with which I had been familiar. The staff trained in this system had little idea of the holistic role which Urban Planning could play. There were some with training or experience abroad who did comprehend âwhat it was all aboutâ, Robert Sowman, Christine Herzog and Christine Caughey for example.

The Social Development section established by Peter Harwood was derived from a âCitizenâs Advice Bureauxâ type model and also saw its role as interfacing with the Maori and Island communities. It is fair to say that many of the politicians and older senior officers regarded the Social Development section as a bunch of âbleeding heart liberals from up the hillâ (the University). It is also true to say that many of the younger staff were politically naive and caused me great deal of trouble in defending them from some senior officers and councillors alike.

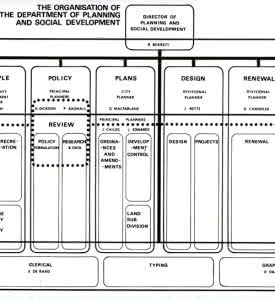

My first task was to organise the Department for the twin tasks ahead, to start with the urgent review of the District Scheme and second to provide a basis for some real planning in a wide range of areas from housing to employment. Then to be able to establish a research and policy basis for all of these. The opposition I encountered, even from some planning staff, amazed me. For example, one said, âit is politicians’ job to formulate planning policyâ another most senior officer said, âwhat has the city got to do with employment policy?â

My first intimation as to what the future held came when I was summoned to the Town Clerk because a young woman, a newly graduated planner, was going around the Council saying âthe new Director will sort you all outâ. On another occasion the Prime Minister urged the Town Clerk to discipline one of the Social Development team for statements he had made.

The real problem emerged and which took me by surprise, because of its lack of professionalism and understanding of the wider role of planning, was the narrow nationalism of some planning staff. Some had been abroad and been well received, but their attitude in New Zealand was âwhat do these overseas experts mean by coming over here taking our jobs?â I was truly and deeply shocked.

I structured the office with the section heads given increased responsibility and a daily meeting between all of them to ensure information was shared across the whole department.

I asked staff to produce a series of reports, housing, recreation, youth, centres, employment etc. What I could not do was to examine the recent City Centre plan which was based on US Central Business District practice of regulation, the fruits of which we see in the present CBD. I did however, after much initial foot dragging, persuade the Council to attempt an experimental pedestrianization of part of the main street, Queen Street. Once the proposal was underway everyone did very good work. John Betts & his team and the whole planning staff and staff of a number of departments (not least the Parks people) did a wonderful job. The people of Auckland thoroughly enjoyed the environment created and used the street to the full. Alas, the politician who had supported the experiment as Chair of the Planning Committee, changed his view during the course of a morning to opposing the whole idea. I suspect he was pressured by traders, fellow councillors and his political masters to withdraw his support, so the experiment was doomed!  This is why Queen Street, Auckland,  after all these years remains such an environment much less attractive than its potential.

Compared to UK I found it very hard to get things done in Auckland and it is fair to say that many of the planning issues I identified remain some thirty years afterwards. However one aspect I discussed at length with Robbie, a single Authority for Auckland, has come about.

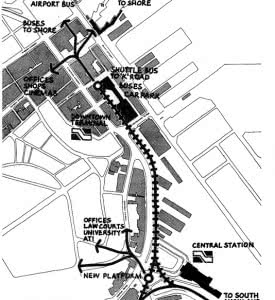

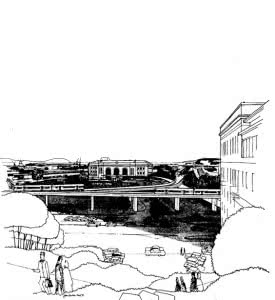

The District Scheme was reviewed after very hard work by the planning staff to achieve the ridiculous legal accuracy demanded by the planning system and the endless objections dealt with. They did a great job under considerable pressure. Many areas such as Grey Lynn were studied and local projects had Planning Briefs prepared and Dr Chris Nobbs undertook planning research studies into a wide range of topics. A project I initiated to facilitate urban rail transit in the Auckland area was to regain suburban rail access to the Downtown at Britomart. This was by an elevated route linking the existing Auckland station to one adjacent to the then GPO.

One of the people who facilitated the Scheme Review process was Bob Drake who led a Graphics Design team who as well as the very detailed planning maps produced much innovative work of quality, unmatched by any other Local Body.

One of the great experiences I had in New Zealand  was to work with Maori people. At that time the Race Relations Conciliator was Harry Dansey a man of great depth and understanding. I was involved in a team attempting to work out a balanced outcome to the Bastion Point issue, I came to the conclusion that neither side wished any compromise. I also had the privilege  to be welcomed on to two Maraes with Robbie and members of my Department, one at Omaio near East Cape and the Maungatapu Marae at Tauranga. In some ways I felt more identity with older rural Maori than I did with some urban European New Zealanders.

As the political colour of the Council shifted even more to the right I found my position increasingly unrewarding with no immediate prospect of a more progressive Council in sight. In addition I sought registration as an Architect in New Zealand. This was after more than 25 years of qualified practice in UK on some of the most prestigious projects of the day, I had to seek approval as to my suitability!

On the other hand I met with a group of people who were talented and innovative in the world of Personal Development, Russell Withers an Architect and Dale Hunter a musician who linked me to others working out radical ideas of living in the modern world and who shared ideas about the environment, see under âFacilitationâ. This too linked to working on the ANZAAS conference at Auckland University with Albertje Gurley, Mike Austin and Mike Pritchard to which I invited Jake Chapman of the Open University to be keynote speaker. As I left to return to UK, the Environment Resource Centre began work and Russell Withers and colleagues established Archangels Architects’ Collective in Ponsonby, an inner city suburb of Auckland.

What with one thing and another I decided to return to UK. I had over time been in discussion with Fred Roche, still General Manager of MKDC, about London Docklands. He was in touch with Michael Hezeltine in shaping the concept of Urban Development Corporations, particularly Docklands and we had hopes to participate in that. However Fred Rocheâs association did not materialize, I contemplated joining one of the earliest âCommunity Architectureâ practices and resigned from Auckland City Council. Between my resigning and starting up in UK, Thatcher was elected, slashing public housing programs. Fred resigned from MKDC to join Conran rather than Docklands and the two people I had known so well personally and professionally, Sheila and Fred Roche separated. It was the low point of my career.

I joined Stephen George and Partners as a Partner for a while, but it was a time of recession and I was without a personal client base. I considered returning to Local Government which was unappetising, even in a senior position it would have been principally to spend time making good Architects and Planners redundant. However I did take the opportunity to complete my Town Planning degree, at what has since become the University of North London.

I decided to enter Academia and I joined the University of Leeds which awarded two unique degrees, âArchitectural Engineeringâ and ‘Civil Engineering with Architectureâ, in the Department of Civil Engineering.